Bend Bulletin: Drought-weary farmers optimistic as snowpack totals soar

As skiers and snowboarders pile into their cars to take advantage of massive snow levels at Central Oregon ski resorts, another group of weather watchers — farmers and ranchers — are cautiously optimistic that the ever-increasing levels of snow will pay dividends for them in the months and years ahead.

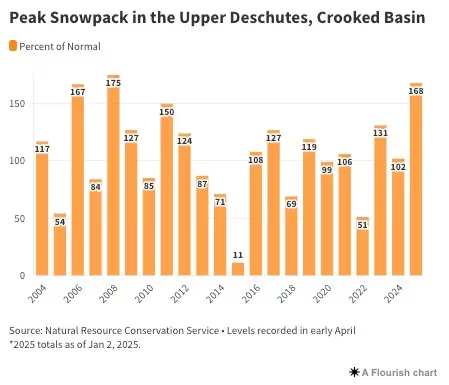

They have good reason for optimism. Snowpack reached 175% of normal in the Upper Deschutes and Crooked River Basin late last month, the highest end-of-year percentage in two decades. The percentage, compiled by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, has since dropped a few points but is still hovering near 170%.

It’s still early days in the winter. But if the snow totals remain close to current levels, it will mark the third straight year of above-average snowpack.

Precipitation factor

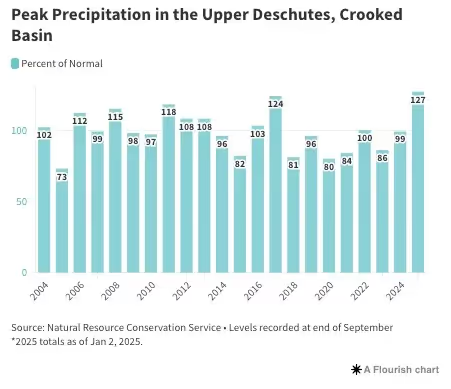

The region needs more than just good snowpack to fill reservoirs, it also needs above-average precipitation (rain and snow), says Joe Kemper, a hydrologist with the Oregon Water Resources Department.

Kemper says total precipitation is even more important than snowpack alone in improving groundwater levels and spring discharge. He notes that 2022 and 2024 were average precipitation years, but precipitation for five of the last seven years was below average.

“We have not had an above-average precipitation year since 2017,” said Kemper.

Kemper identifies 2023 as a particularly misleading year. At that time, the Deschutes Basin had above average snowpack in mid-April but was well below average for total precipitation.

“That is a net negative to groundwater levels and spring-fed streams like the Metolius,” said Kemper.

Climatologists are hopeful that the region is absorbing enough rain and snow to boost the all-important precipitation index.

“Over the past two weeks, the region has experienced surplus precipitation, accompanied by significantly above-average snowpack in the Cascades and Ochoco mountains,” said Larry O’Neill, an associate professor at Oregon State University’s College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science.

“While the wet season still has about four months remaining, leaving room for potential dry spells, the current trajectory indicates a good likelihood of favorable water supply for the upcoming growing season in Central Oregon,” he added.

Possible water allocation increase

These conditions could persuade irrigation district board members to set a higher water allocation for farmers and ranchers in North Unit Irrigation District, this region’s largest, in terms of commercial farming acres.

Discussions around water allocations percolate in February but likely won’t be confirmed until March. In recent years, allocations for North Unit farmers in Jefferson County have been meager, only enough to plant crops on half a farm, or less.

Atmospheric river burying mountain areas

Read more: Atmospheric river burying mountain areas with snow in Central Cascades

More water this year could help swing the fortunes of those farmers who have managed to stay in business through years of drought, which hit hardest from 2019 to 2021. With more water this year, increased crop sales could help protect farmers against low prices for many of the commodities grown in Jefferson County.

“We are excited for the moisture that Jefferson County has been receiving in addition to the great snowpack,” said Josh Bailey, the general manager for North Unit Irrigation District. “Things are most definitely trending in the right direction, and we do anticipate a better water season.”

Low commodity and seed prices

Marty Richards, a North Unit farmer, is optimistic this winter’s storms will pay dividends for farms in Jefferson County.

“If it continues the way it’s going we should be well and truly out of the drought for the next year because the way our basin works, it’s on a two-year cycle. So whatever we’re getting this year will also give benefits from next year,” said Richards.

But even if more water is headed that way, some farmers will have tough decisions to make in how to manage it due to low commodity prices. Farmers who typically grow wheat or hay, both common in Jefferson County, aren’t likely to turn a profit due to the depressed prices.

After rising sharply during the pandemic and into 2022, wheat and hay prices in Oregon are now at five-year lows. Global supply chains, market conditions, demand and other factors beyond local control impact both.

Prices paid for grass seed crops, also widely grown in the area, are also low, according to Albert Sikkens, the site manager for Pratum Co-op branch in Madras. Prices spiked during the COVID pandemic but have since fallen below historic averages.

“We’ve had our day in the sun, we are also dealing with our day in the darkness,” said Sikkens.

Taking a gamble

Costs are another impediment to turning a profit — farmers are paying more than ever for electricity and labor.

“We raise wheat around here and it’s below the cost of production,” said fifth-generation farmer Evan Thomas, also a Jefferson County farmer. “The price of water, power, labor, fertilizer, chemicals. Everything is up.”

But despite the headwinds, Richards said he might “make a gamble” on hay and wheat this spring, hoping that prices could climb later this year. Even if he doesn’t plant these crops, extra water will help to grow a cover crop to maintain soil health.

It could also help in planning next year’s crop. Richards may use the water to prepare land that has been sitting idle . In recent years he’s left 40% of his acres fallow due to drought, but knowing that more water is on the way allows him to prepare half of those acres for crops.

He’d like to get more ground prepared for perennial crops, such as grass seed, which has more value compared to wheat or hay. He plans to get these seeds in the ground gradually so the crops don’t all come out at the same time.

“I wouldn’t try to do 100% because it isn’t a good way to do things,” he said. “You want to work it back in gradually.”